In 58 BC, the Helvetii, a Celtic tribe living in what is now Switzerland, attempted to migrate westward to a more fertile area in Gaul. Their route would take them through Roman territory, and so they sought safe passage from the governor of the province. Unfortunately for them, the governor was a highly ambitious, deeply indebted man—Julius Caesar. Seeing an opportunity for personal gain and glory, Caesar granted permission for the Helvetii to pass through, only to secretly gather 30,000 soldiers, chase the tribe down, and attack. In his Commentarii de Bello Gallico, Caesar boasted that of the 368,000 men, women, and children who sought to migrate, only 110,000 survived.

Under the pretext of regional instability, Caesar launched a full-scale invasion of Gaul. Over the next six years, he waged relentless warfare on the Celtic tribes. By the time of the final battle in 52 BC, over one million Gauls had been killed, another million enslaved, and entire populations wiped out. As a result, Rome’s borders stretched from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Rhine in the east, and from the Mediterranean Sea in the south to the English Channel in the north.

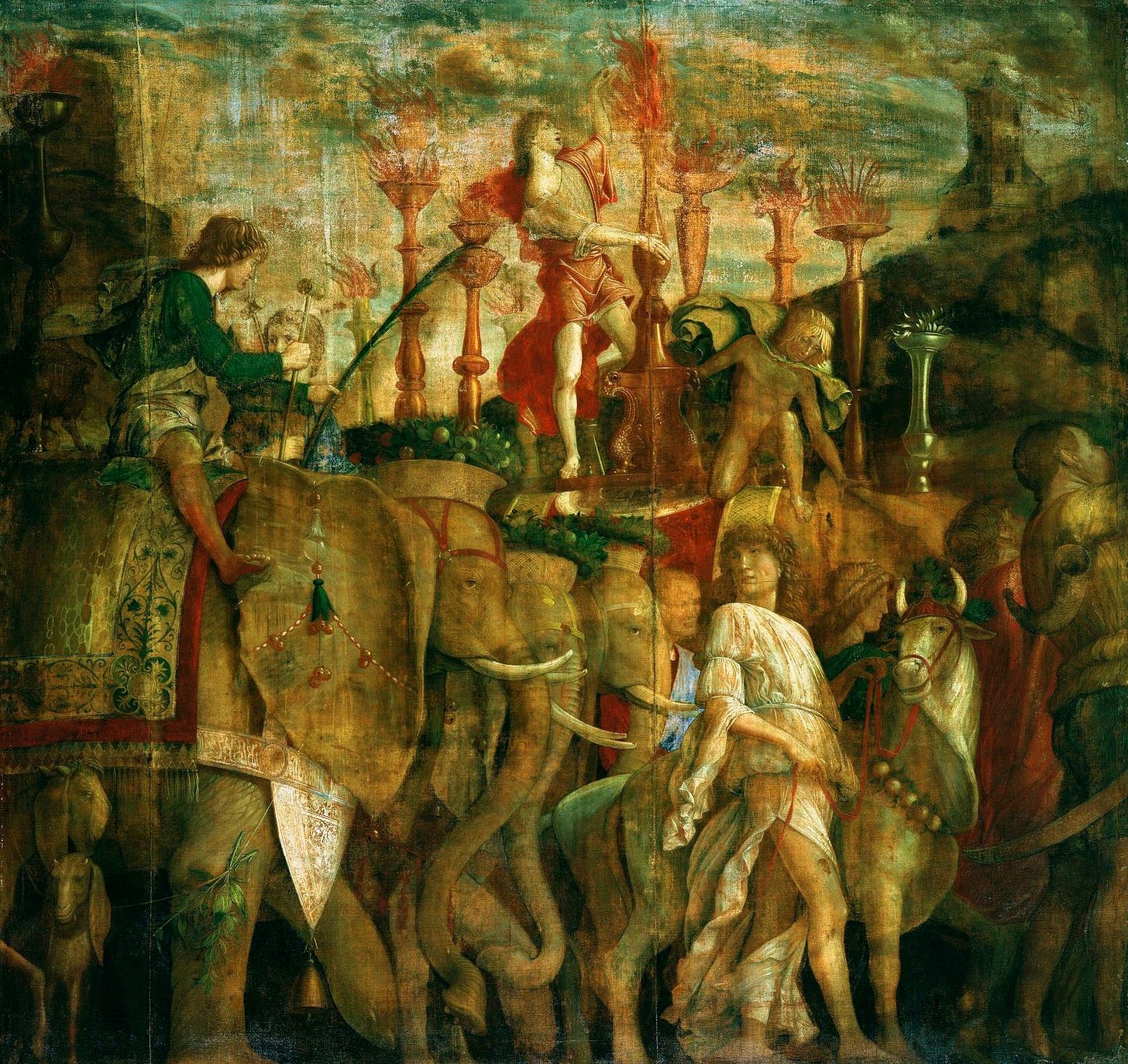

Caesar was rewarded for his conquests with a triumph, a grand parade through the streets of Rome. Ever the showman, Caesar rode in a gleaming chariot, dressed in a purple and gold toga, a laurel crown on his head, a scepter in hand. In imitation of Jupiter, he painted his face red. Alongside him his soldiers sang bawdy songs of praise (“men, keep your wives close, the bald adulterer is back and triumphant!”), carried captured treasure and loot, and held up flags and banners depicting victorious battles. Forty elephants and other exotic animals were paraded to delight the crowd. Behind Caesar's chariot walked captured prisoners and slaves, including Vercingetorix, the Gallic chieftain, who was publicly executed by strangulation.

Caesar’s adopted son and successor, Octavian, expanded his father’s territorial gains and transformed the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire. With the absence of major wars, Octavian’s reign initiated what became known as the Pax Romana—the Roman Peace. The term pax derives from the concept of a treaty, but in Roman military contexts, it meant “to pacify,” “subdue,” or “subjugate” rebellious territories. Pax was something achieved through conquest and maintained through overwhelming domination—order imposed through violence. As the first-century historian Tacitus wryly noted, ubi solitudinem faciunt, pacem appellant—“They make a desert and call it peace.”

Octavian took power in 27 BC and adopted the title Caesar Augustus. Thirty years into his rule, he called for an empire-wide census. In a remote part of the empire, a young woman, unexpectedly pregnant with her first child, traveled with her new husband to fulfill the registration requirement. The birth of this son in a humble barn was heralded by a host of angels proclaiming “peace on earth.” But despite many of his people’s messianic expectations, this child did not come to replace Pax Romana with a Pax Judea. Instead, he would teach a radically different vision of peace—one not born of domination but of love, sacrifice, and reconciliation.

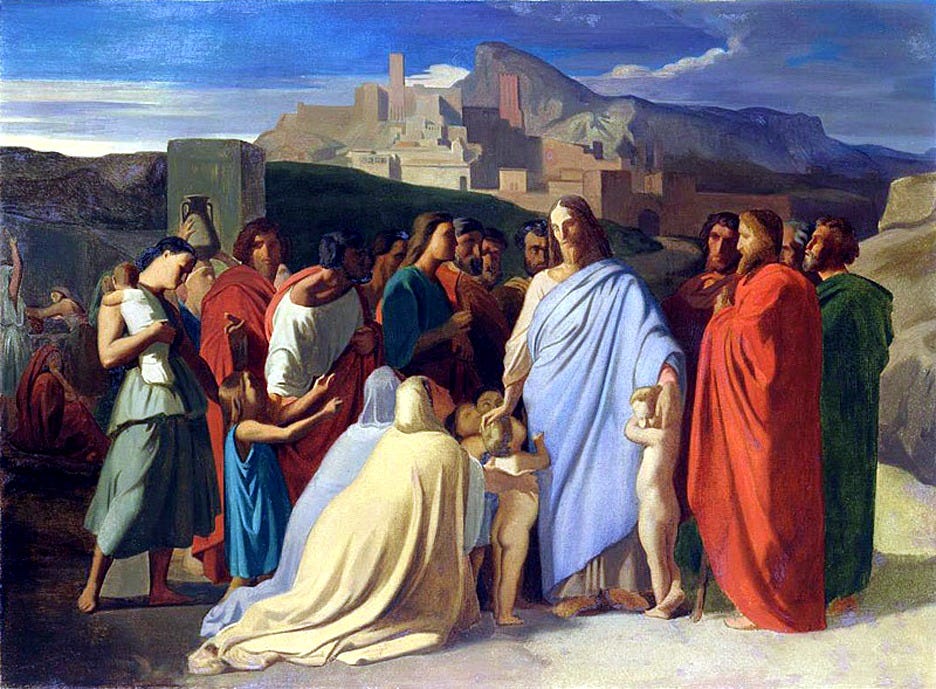

It is not incidental that Jesus was born at the very height of Roman power. The entire message of the gospel can be read as a revolutionary inversion of the way of Caesar. Caesar sought glory through the defeat and death of his enemies, while Jesus taught that we should love and pray for them. Caesar accumulated wealth and honor, while Jesus wandered homeless and counseled giving away riches to the poor. Caesar celebrated the strong and powerful, while Jesus ministered to the sick and the outcast. Caesar pursued greatness by ruling over others, while Jesus taught, “Whoever wants to be great among you must be your servant.”

At a final meal with his anxious and fearful disciples, Jesus reassured them: “Peace I leave with you; my peace I give you. I do not give to you as the world gives. Do not let your hearts be troubled and do not be afraid.”

Jesus would have used the Aramaic version of the Hebrew word shalom (שלום). Shalom means far more than absence of conflict; it conveys wholeness, completeness, and well-being in all aspects of life, both physical and spiritual.

The theologian Cornelius Plantinga describes shalom as “the webbing together of God, humans, and all creation in justice, fulfillment, and delight . . . a rich state of affairs in which natural needs are satisfied and natural gifts fruitfully employed, one that inspires joyful wonder.”

The peace the world gives is pax. The peace of Christ is shalom. Pax is imposed by power, maintained by hierarchy. Shalom is cocreated in friendship. Pax seeks control, shalom seeks at-one-ment.

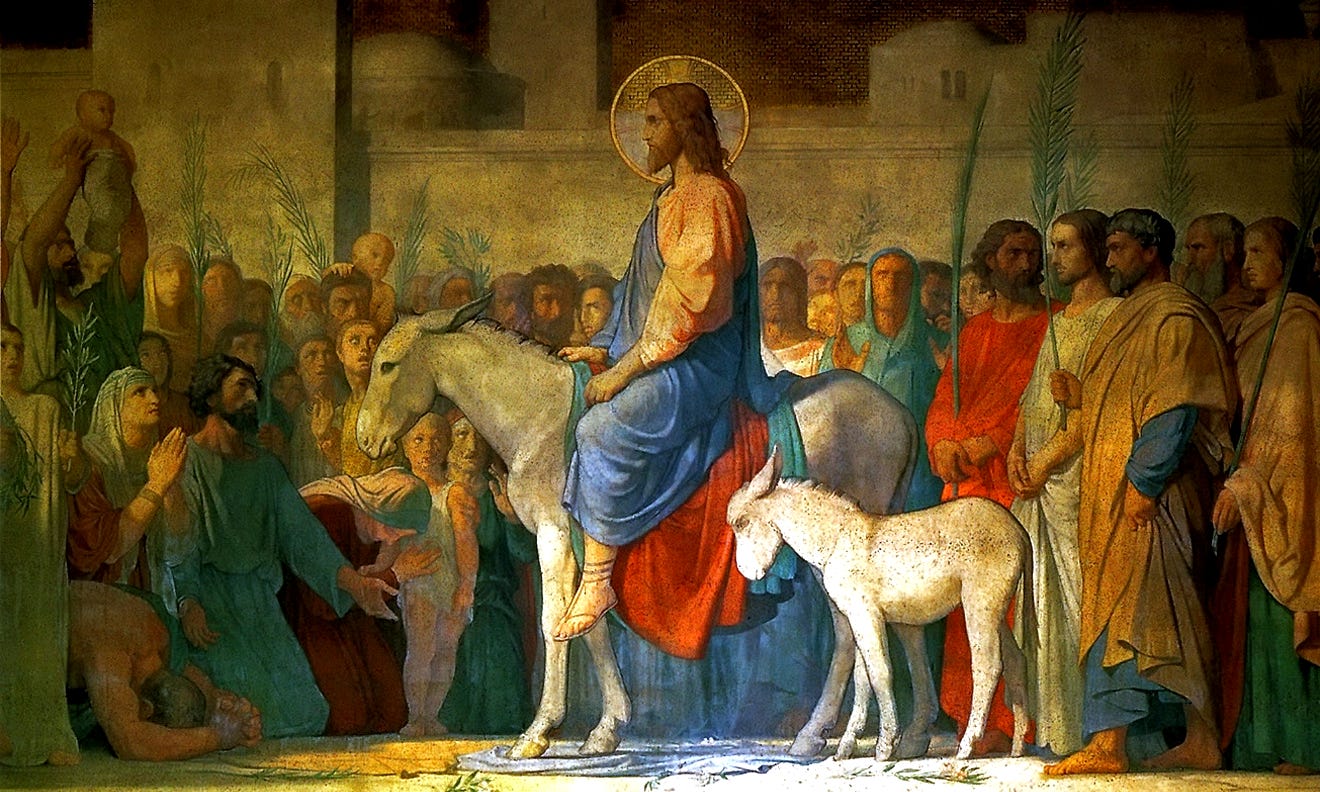

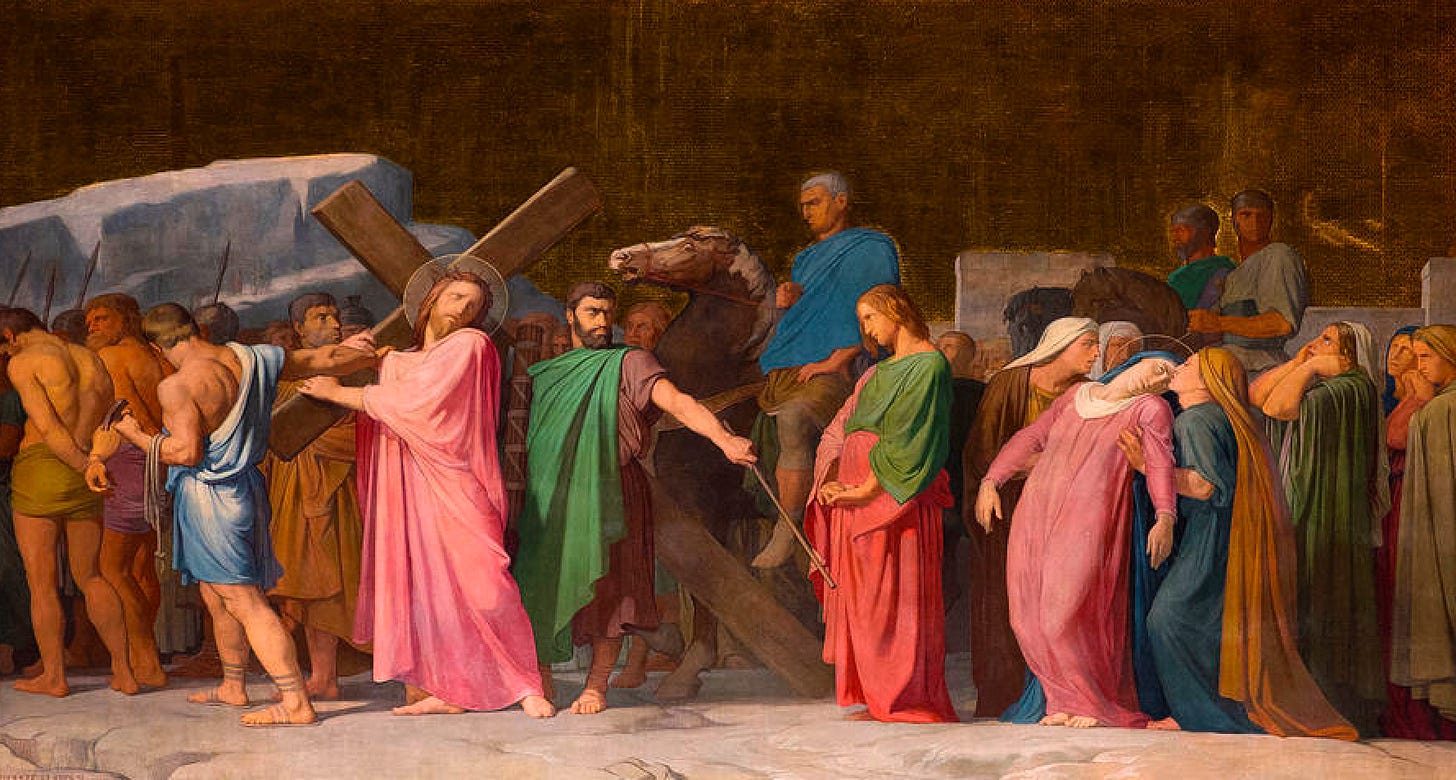

These contrasting visions of peace become most vivid when we compare Caesar’s Gallic triumph to Jesus’s Passion procession. Caesar was honored for the number of people he had conquered, subjugated, and killed. When Jesus entered Jerusalem on Palm Sunday, he was surrounded by those he had healed, taught, and set free. Caesar rode in a grand chariot drawn by four white horses; Jesus rode a donkey. Caesar wore a purple and gold robe; Jesus had his robe stripped away. Caesar wore a gilded crown and painted his face red to mimic divinity; Jesus wore a crown of thorns, his face red with his own blood. Caesar carried a scepter; Jesus carried a cross. Caesar executed his captives; Jesus forgave his captors. In the climax of his triumph, at the top of the Capitoline Hill, Caesar sacrificed a bull; at Calvary, Jesus sacrificed himself.

Caesar or the Cross. Pax or shalom. We all must choose.

In the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus invites us to join him in his path of shalom. “Blessed are the peacemakers, for they will be called children of God.”

Making shalom is a dynamic response to the needs of the people and communities we are bound to. It requires creativity, action, and courage. The enemy of shalom is fear. Do not let your hearts be troubled and do not be afraid. Fear makes us passive. Fear isolates us. Fear leads us to see each other not as friends to cherish but as enemies to defeat. It was fear that caused the chief priests to reject the Messiah before them and shout to Pontius Pilate, “We have no king but Caesar!”

The antidote to fear is presence. When the Israelites camped in the wilderness after their exodus from Egypt, Moses ascended Mount Sinai to speak with God. In one encounter, God gave Moses a prayer for Aaron and his sons to offer the people:

The Lord bless you and keep you; the Lord make His face shine on you and be gracious to you; the Lord turn His face toward you and give you peace.

Peace flowed from the shining face of God. Peace is relationship. Absence of conflict may be a starting point, but what we really seek is the deep presence of love. We long to be in face-to-face communion with our friends, our family, and above all, with our God. This is a peace that no empire can impose and no sword can secure—a peace that comes through the Prince of Peace Himself. As Paul wrote to the saints in Ephesus, where Jewish and Gentile Christians were struggling to trust each other: “For He Himself is our peace, who has made the two groups one and has destroyed the barrier, the dividing wall of hostility.” And when we become one, we will find ourselves at last in Zion—the New Jerusalem, the eternal City of Shalom.

This essay is the introduction to Wayfare Issue 5. Learn more about the issue and subscribe to the print edition here. And if you’re in Utah, join us for the issue release party on May 2. RSVP here.

Art by Andrea Mantegna and Jean-Hippolyte Flandrin.